By Stephen Bryen

It was a brutally hot day in July, 1864 –the twelfth to be exact. President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary left the Soldiers Home at 140 Rock Creek Church Rd and went by carriage to Fort Stevens. The Lincolns were staying in a cottage at the soldier’s home to escape Washington’s oppressive summer heat. The trip to Fort Stevens on 13th Street was arranged at Lincoln’s insistence because a battle was raging between Confederate and Union soldiers focused on taking the fort.

The Confederate attack was serious. By this time Richmond was facing General Grant’s army and rebel General Robert E. Lee was trying as much as he could to relieve pressure on the Army of Northern Virginia and protect Richmond. He formulated the idea of a flank attack to divert Grant’s troops to protecting Washington. The Second Corps of Northern Virginia, led by Lt. General Jubal Early, swung around to the west and headed toward Frederick Maryland. From there they would move down toward Silver Spring and then attack the fort.

In the Civil war Washington had a belt road around its perimeter that included a number of forts and posts. The roadway is still there and it is appropriately called Military Road. The road provided the communications and logistical support needed to protect Washington.

The fight around Silver Spring and the broader area, including the Sligo Creek, started on July 11th with skirmishing. There was some looting carried out by the Confederates, indicating that Early’s forces were not well disciplined or trained. One of the mansions they looted belonged to Montgomery Blair –it yielded lots of liquor that slowed the confederate operation. The real fight got underway on the afternoon of the 12th of July, rather late in the day.

Lincoln, the story is famously told around here, stood next to a Union Army surgeon watching the skirmishing when a sniper, recognizing who he was, tried to shoot him. He missed. Instead the surgeon was wounded.

Lincoln was rushed away from the exposed area. In fact, the situation was so worrisome to the Army and the White House, that should Fort Stevens need to be evacuated, protecting the city would become extremely difficult. A steamer on the Potomac was waiting to whisk Lincoln, his wife, and cabinet officers away should the emergency grow.

In the battle, now in the late afternoon, confederate forces began to take heavy casualties and showed no indication they had the ability to move forward. Had they continued on, the only result would have been more dead and wounded.

In the aftermath, the Union army buried the dead –from both sides. About 40 Union Soldiers who died in the battle today are interred in a small cemetery on Georgia Avenue named the National Battleground Cemetery. Many are from New York.

According to an historical trust document supplied by the Grace Episcopal Church, among the confederate troops killed, 17 were buried in a shallow grave in the Brightwood neighborhood of the District of Columbia. After the war, the pastor of Grace Episcopal Church, James Avirett who had served as a chaplain with the Confederate 7th Virginia Cavalry, noticed the poor condition of the graves of the hastily buried soldiers, and began a campaign to give the soldiers a proper burial at Grace Church Cemetery. Reverend Avirett had the soldiers exhumed, and the remains were placed in six coffins for transport. At the time of exhumation, it was discovered that the majority of the soldiers were no more than teenagers, three of whom were officers and 14 privates. The only soldier identified was James B. Bland of Highland County, Virginia. Bland had served with the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry. With consent of the vestry on December 11 , 1874, the remains were re-interred between the primary entrance of Grace Episcopal Church and the turnpike. James B. Bland was placed in the northernmost grave in case his family ever came in search of his remains.

The church decided to hold a proper funeral for the dead confederates because it was felt when they were hastily buried in 1864 they were not afforded a Christian burial.

In 1894 a small monument was erected. It is located at the intersection of Georgia Avenue and Grace Church Road at the front of a small cemetery adjoining the church.

This week Black Lives Matter defaced and toppled the monument.

Credit: WUSA9

The grave marker was toppled late Wednesday night, June 17th.

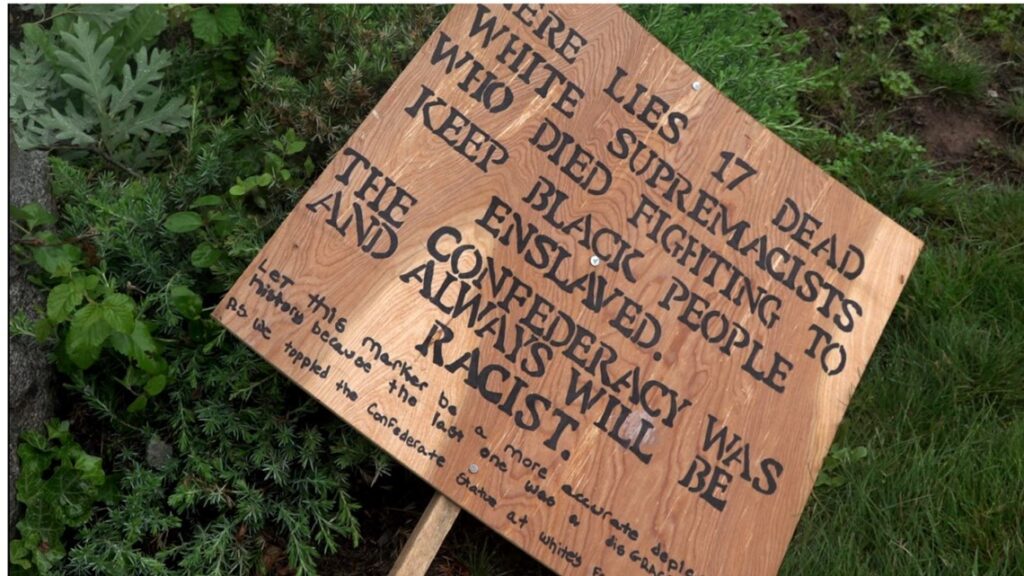

They also left a message that was prepared well ahead of time, demonstrating this was a planned grave desecration and not an impulsive or random event.

An Act of this kind is not excusable.

Lincoln asked for malice toward none. BLM’s act is uncivilized and un-Christian –and full of malice. BLM should be condemned for destroying graves.